By Yvette Pecha

Electric cooperative director recalls life in rural Michigan—and how it changed with electricity

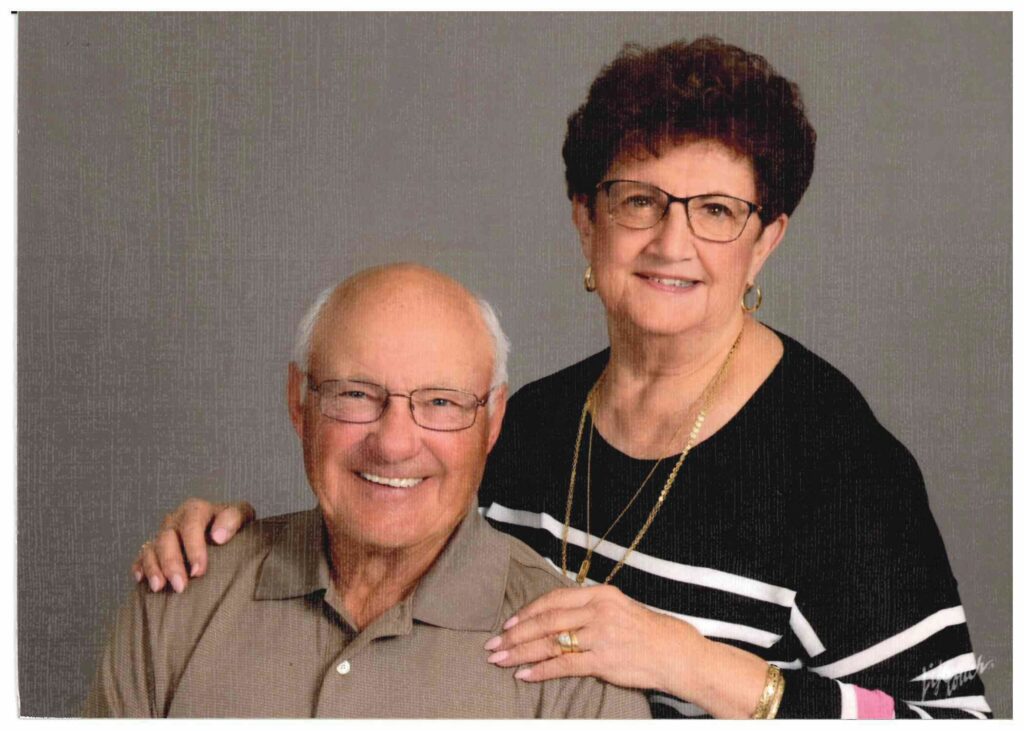

Louis Wenzlaff is somewhat of a luminary in the Thumb Electric Cooperative (TEC) service area. He was born and raised in Kingston, Michigan, and has spent his entire 87 years of life in the town, working in industries including farming, teaching, banking, and health care. As a TEC board member since 1977, he also has played a large role in ensuring cooperative members receive efficient and reliable electricity—something that, for good reason, he doesn’t take for granted.

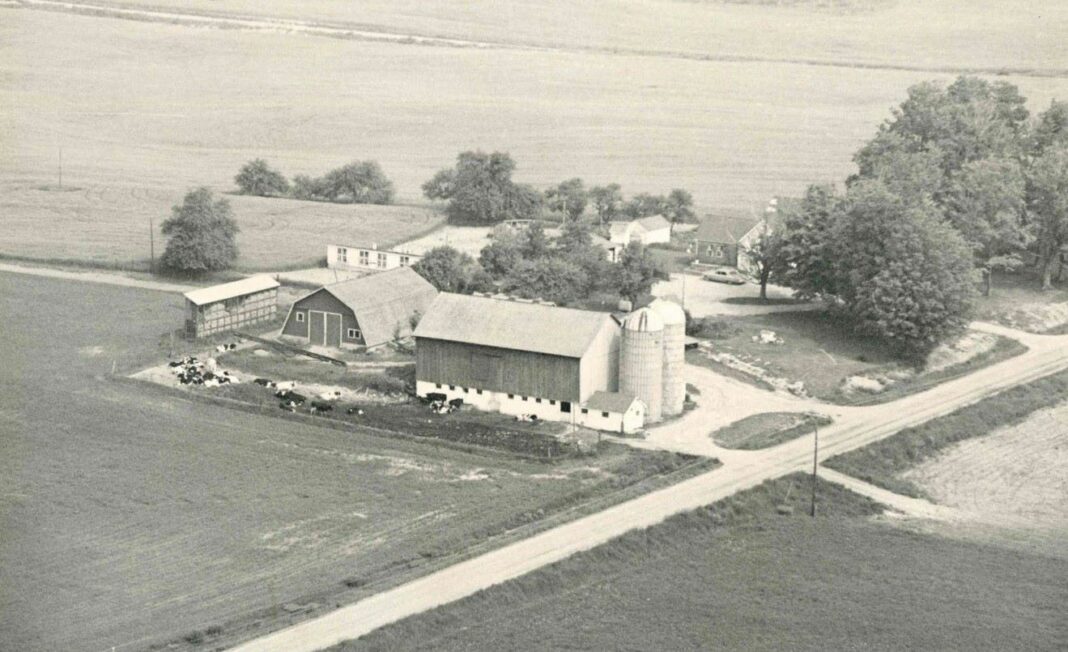

The Wenzlaff family heritage in Michigan began when Louis’ grandparents, who were both German-born and had immigrated to Illinois, heard of a 120-acre farm that was for sale in Kingston. The eight children they raised on that property included Louis’ father, also named Louis. Louis Sr. moved to Detroit when he was 16 years old to work for Cadillac, but when the Great Depression hit in 1929, he moved back home to help prevent his family from losing the farm.

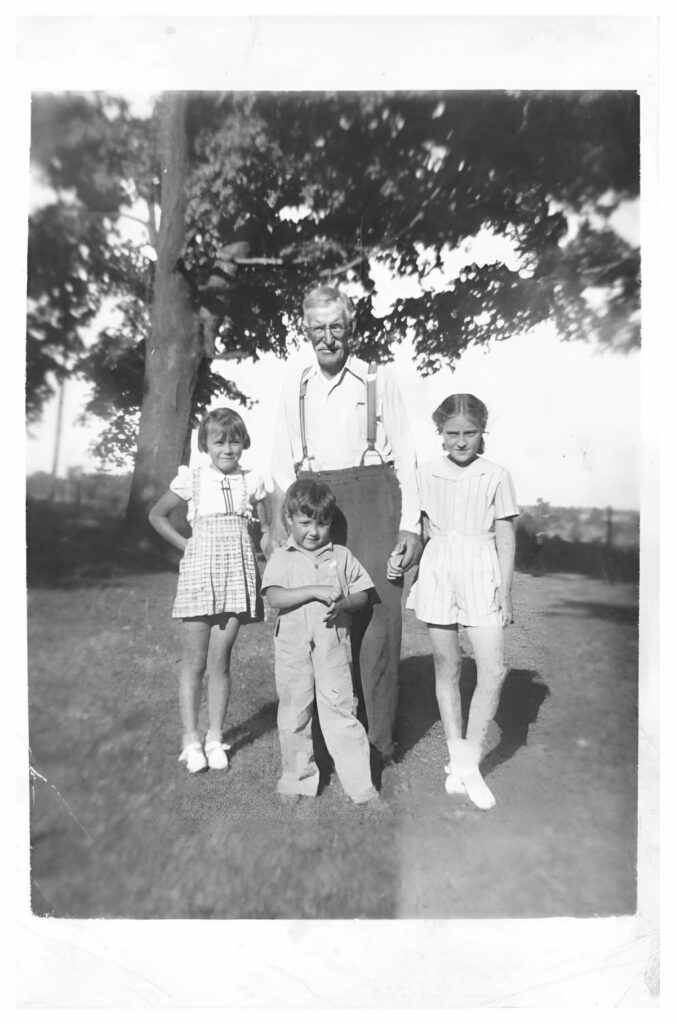

Louis Sr. met his soon-to-be wife Elizabeth at the country school, where she was a teacher and he was in charge of starting the potbelly stove fire on winter mornings. As was typical at the time, Louis Sr. and Elizabeth lived at the home of Louis’ grandparents, where they welcomed two daughters and then Louis. All three children were born in the house with the help of their grandmother and local midwives. One of Louis’ earliest memories is a momentous one: In 1941, when he was 4 years old, the Rural Electrification Administration (as TEC was known as the time) brought electricity to the farm. Louis said he remembers it “like it was yesterday.”

“You have to think of it,” Louis said. “We had no electricity, no running water, no plumbing, no nothing—it completely changed our lives.” The family’s first priority was to put a few lights in the house, followed by more lights in the barn. Using the well on the property, they then installed plumbing. Their first big appliance purchases were a refrigerator and a wringer washing machine. Next came a toilet—replacing the “three-holer” that Louis said they had in their outhouse because the family was so big. The introduction of these luxuries required the whole house to be remodeled. “They put in a bathroom and kitchen and septic tank—before, it had basically just been four walls,” Louis said.

Productivity on the farm increased for the Wenzlaffs due to many factors, but one major difference was in dairy production. Louis said they had 12 cattle that had previously been milked by hand by the light of two kerosene lanterns. “But then we got a machine from Sears-Roebuck that milked two cows at one time. It was wonderful, really,” Louis said. Adding a milk cooler also saved enormous quantities of time and energy. The family continued to slowly add appliances and new technologies, but they still lived a rather primitive lifestyle. Louis and his sisters would bathe about once a week, in the wash tub outside in the summertime and in front of the kitchen stove in colder seasons. “We just had to learn all the practical things we had to do to survive,” he said. The Wenzlaffs didn’t have much money, but that didn’t stop them from having fun. Louis said his aunts and uncles would visit every weekend. “Mother would play piano, and Dad would call square dances—that old house would just shake,” he said.

The farming life clearly suits Louis as he has, in some capacity, done it all his life. But he dipped his toes into several other careers as well—usually at the behest of others. Louis attended college for three years but left to work with his maternal grandfather, who was a carpenter, and procured a second job at a local lumberyard. His work at the yard consisted of installing plumbing, heating, and electrical services into local homes. He helped set up the area’s first ready mix concrete plant and delivered the cement to farmers. “As far as practicality, I learned more in those four years than I did in the rest of my career,” he said.

His carpentry days ended when the Kingston Community Schools superintendent asked him if he wanted to work for the district. He taught bookkeeping and typing there for four years and was a coach for various sports. (Upon leaving the district, he served on the school board for over 30 years.) While teaching, Louis decided to continue with college and earned a bachelor’s degree in education from Central Michigan University…but then a new opportunity arose. “The guy I worked for at the lumberyard was the president of the bank board, and he said, ‘Why don’t you come run the bank?’” Louis said. “I didn’t have much knowledge, but I learned it and I stayed there for 23 years.” He was the CEO until Kingston State Bank was sold, upon which time he moved on to constructing modular home interiors for two years. And then yet another industry came calling for Louis: A former bank customer who was on Sanilac County’s social services board asked Louis if he wanted to oversee the county nursing home. Louis was the administrator of that nursing home for 22 years.

In 2013, Louis finally retired. But he continues to have an impact on the community and stays active in his personal life as well. Louis credits his longevity to “working hard and playing hard.” He and his wife Sharon have five children, two of whom help him out on his hobby farm. And, as mentioned, this is his 47th year of serving on the TEC board, which he says he enjoys for a number of reasons—including the travel benefit. Louis said he was always too busy with work and the farm to go anywhere outside of Michigan, so he’s been grateful for the opportunity to attend national director conferences. Louis certainly has a busier life than the average 87-year-old man, but rest assured, he is looking to slow down. “I might give up golfing,” he said with a laugh.