When we think of animal rescue efforts, we likely picture a pile of fluffy kittens or the soulful chocolate eyes of a puppy needing a home.

So, if you have ever seen the diamond-shaped pupils of an adult sturgeon swimming by at six to seven feet long—it’s a lot less precious and a lot more prehistoric. Perhaps it’s that other-worldly quality that makes the folks at Sturgeon for Tomorrow so passionate about their mission.

A nonprofit started in 1999, Sturgeon for Tomorrow manages annual goals and engages in partnerships to keep the lake sturgeon of the Great Lakes area alive and thriving. Its run entirely by volunteers, including Brenda Archambo—president of the Black Lake chapter of Sturgeon for Tomorrow—who saw her first mammoth fish as a kindergartener when she went ice fishing with her father on Black Lake located in Presque Isle Electric & Gas Co-op’s service territory.

“I will never forget looking that sturgeon in the eye,” said Archambo. “There was this commotion coming from one of the ice shanties as they pulled out this enormous fish. It was like seeing a dinosaur in real life.”

That experience traveled with Archambo into adulthood, as she started hearing stories of over-fishing of sturgeon, particularly as a source of caviar. In the mid-’90s, she read about a strategy to rehabilitate the lakes where sturgeon lived, and she began writing to the director of the campaign. For an entire year.

“I became really invested in saving the sturgeon,” said Archambo. “Maybe it was my childhood spent in nature and receiving so much from being in it. I became focused on giving back.”

Archambo began reaching out to ice anglers in Michigan. She understood that preserving sturgeon was as important to them as those looking to protect the endangered fish. The anglers agreed to skip an entire fishing season and became early volunteers who gathered along the banks of Black Lake as part of the guardian program. This eventually included hundreds of volunteers over the five-week spawning season, patrolling the water to deter poachers. Working in conjunction with law enforcement and conservation officers, the volunteers spend over

8,000 hours annually in their efforts.

“We’ve come a long way since the beginning,” said Archambo. “We’re this great group of people who care. It’s amazing what a caring community can get done.”

Archambo credits the many individuals, organizations, and agencies with the success they’ve seen in sturgeon numbers rebounding. She describes it as a four-legged stool consisting of management (regional, state, and tribal agencies), assessment (academic researchers and scientists), law enforcement (regulation and officers), and progressive public involvement.

“If any one of those legs weakens, we tilt,” said Archambo. “But when we’re all doing our part, staying involved, and acting, we are able to stabilize the entire process.”

The balance Archambo is referring to is managing the current sturgeon population, with nearly 1,100 adult sturgeon in the system due to the efforts to increase safeguards and restock. Sturgeon can have long lives, with males living to approximately 80 years old and females surviving up to 150 years if protected. The total population is merely 1% of its historical range, and Sturgeon for Tomorrow is committed to changing that trajectory.

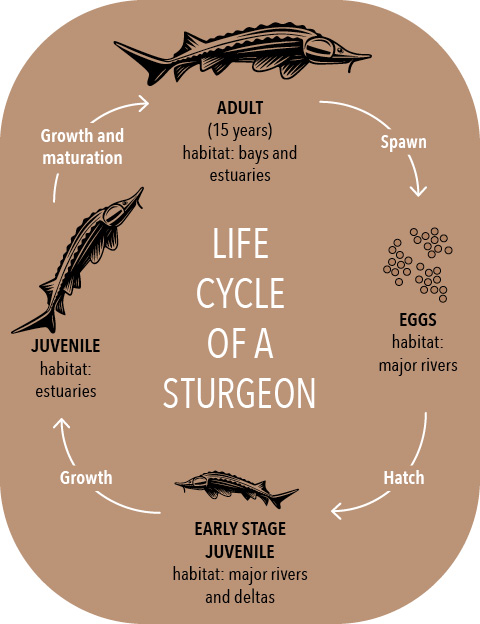

“The goal is to save our current population and protect future spawning,” explained Archambo. “Sturgeon don’t begin producing until they reach 20 years old, so the life cycle is something it will take a long time to fully understand and adjust our planning to support. The key is to keep vigilant.”

With annual plans, cooperative agency efforts, and committed volunteers, Sturgeon for Tomorrow is well on its way to saving the endangered sturgeon. But Archambo also understands that part of the mission is passing on the passion to a new generation. That’s why Sturgeon for Tomorrow’s educational wing is particularly vital. It includes a program called Sturgeon in the Classroom that vets classrooms to become stewards of small sturgeon from the hatchery. The class adopts, raises, learns about, and eventually releases the sturgeon back into a natural habitat.

“Watching volunteers from a preschooler to a retired veteran work alongside in the open air, seeing the cooperation of so many groups and organizations—I love what we do,” said Archambo. “I think we’re all a little bit in awe of the difference we can make together because we know none of us could do it on our own.”